view as list

In their early days, PBYs, or patrol bombers, were the fastest thing in the sky. Designed to float on the seas and fly in the skies, the floating bombers were used for a variety of missions from bombing to patrolling to search and rescue missions.

PBYs were not designed to fly in close formation. That was the case seventy five years ago off the coast of San Diego, California. Two ocean skimming planes collided in mid air. Ten naval airmen were killed. One of them, Julian Rawls, was a Dublin man. At the time, it was the worst air disaster in the history of the United States Navy.

The Navy brass in Washington were planning for a possible invasion along the western coast of the United States in the latter years of the 1930s. Although the true amphibious attack never materialized, the Navy kept preparing for the worst case scenario.

Rain was forecasted on a cool, cloudy Ground Hog Day evening on February 2, 1938. With a moderate northwesterly wind was blowing in to the shoreline, it was not going to be a good day for flying. Flying at night would be worse, much worse.

More than 100 sea going vessels, 250 planes and 40,000 men were engaged in war maneuvers some 70 miles southwest of Point Loma, California. The San Diego Union reported that nearly all of the personnel in San Diego were out at sea participating in the war games.

The time was 20:37 hours. Pitch black, moonless skies, permeated with low lying, rainy, rapidly moving clouds and augmented by heavy squall winds, obscured the visions of the flying boat pilots. Lt. Elmer Cooper, (LEFT) flying 11-P-3 and Lt. Carlton Hutchins flying 11-P-4 began to drift dangerously close to each other. Then in a deadly instant, the two flying boats became entangled.

Sailors as far away as San Clemente Island saw the brilliant flames illuminating the dreary night sky. Crash boats of the U.S.S. Pennsylvania picked up the four survivors; D.B. McKay, V.O. Hatfield and L.S. Carpenter, all from the crew of 11-P-4. J.H. Hester, Rawls’ counterpart aboard the other doomed plane, survived the initial collision but later died aboard a hospital ship.

Chief Machinist’s Mate, V.B. McKay, one of the three survivors, told friends, “We were flying through a rain squall with no visibility. We were flying in close formation between 3000 and 4000 feet above the ocean.”

“The plane 11-P-3 nosed into our tail. The other ship caught fire. Ours went into a spin and fell toward the ocean,” said McKay, who suffered a broken leg.

“Lt. Carleton Hutchins (the commander of 11-P-4) ordered all of the crew to abandon ship. All of them got free either by using parachutes or in some other fashion. Two or three of us tried to hold Lt. Hutchins above water. He was unconscious. We managed to keep him up for about half an hour and then we finally had to let go,” McKay recalled.

Lt. Hutchins, (LEFT) who remained at the controls until his men bailed out of the crippled plane, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism. The ultimately noble citation read, “Although his plane was badly damaged, Lieutenant Hutchins remained at the controls endeavoring to bring the damaged plane to a safe landing and to afford an opportunity for his crew to escape by parachutes. His cool, calculated conduct contributed principally to the saving of the lives of all who survived. His conduct on this occasion was above and beyond the call of duty.”

Lt. Hutchins was further honored in 1942 when the destroyer, the U.S.S. Hutchins was named in his honor. Lt. Cooper was also honored with a destroyer, the U.S.S. Cooper named in his honor.

The seven-man crew of 11-P-3 never had a chance. Radio man Rawls barely had time to send out a Mayday message. P-3 Pilot Cooper did all that he could, never having the time to think about his beloved wife Frances and son Petie back at home. The 105-foot wide plane burned and exploded into unrecognizable pieces.

Four fortunate survivors of 11-P-4 had enough time to don their parachutes and jump to safety. There were no survivors aboard 11-P-3. The bodies of the ill-fated crewmen of 11-P-3 were found except for Julian Rawls, John Neidsweicki and Martin Woodruff.

Julian Rawls, (LEFT) a native of Dublin and then a resident of Chula Vista, California, had been in the service for seventeen years, two years in the Army and fifteen years in the Navy. Rawls, a radio operator, was eligible for retirement in 1940.

Rawls, the husband of Evelyn Prince Watson, was born in Dublin in 1901 . A son of O.H.D. Rawls and Julia Rawls, Julian grew up in a couple of homes on North Jefferson Street.

All movements of the fleet ceased. Radio silence was lifted to initiate a search for survivors. The search lights of 98 ships illuminated the crash zone in hopes of spotting survivors, any survivors. At dawn, every ship, boat and plane were pressed into search and rescue operations. No signs of survivors, victors, or Rawls’ PBY were ever found. The search was called off the following evening.

The war games resumed.

Admiral Charles Blakey instituted an investigation of the cause of the collision and promised that the regrettable and costly accident would help the navy to prevent future accidents like this one.

The collision and resulting crashes of two PBYs were reported to be the greatest loss of a heavier than air aircraft disaster in the history of the United States Navy. Eleven men died that fateful night.

Training accidents, a fact of life in the service, were common in World War II. The collision was the third in six months in the area, leaving an even two dozen men dead.

The body of Dublin’s Julian Rawls, was reportedly never found. There is a cenotaph marker in North view Cemetery (Sect. D, Row 3) to mark the life of this man, perhaps our county’s first casualty of World War II.

Yet, his grave marker does not indicate that he was a member of the U.S. Navy - only a worn tattered flag indicates that he was a patriot. And, Rawls’ name is not inscribed on the World War II monument on the courthouse lawn. Now and forever, let us remember Julian Rawls and his fellow men who gave their lives to protect our country, seventy five years ago this week.

When Giants Played on Its Field

On a warm, early spring Friday afternoon, a baseball game was played. Not just an ordinary semi-pro game for the folks in Eastman, Georgia, it was nine-inning game between the Detroit Tigers of the American League and the Boston Braves of the National League. Four thousand avid baseball fans filled every seat and lined the perimeter of the newly constructed ball field to see several of the grand ol’ game’s finest play America’s greatest pastime.

In the days before routine airline travel and obligatory spring training sites in Florida and Arizona, many teams spent their pre-seasons in places like Macon, Augusta and Columbus, Georgia. Two of those teams, the Tigers and the Braves, planned a 17-game series beginning in Columbus, extending through the Carolinas, and ending in Maryland before the start of the 1920 season.

The Boston Nationals took the first three games of the series by good margins of the 3, 5, and 3 runs in Columbus, Moultrie and Valdosta. Eastman was the fourth stop along the way. Dublin, a much larger city, would have normally been on the list. The Braves scheduled games there in 1917, 1918 and 1919. The 1917 game with the Yankees was rained out. The 1918 rematch was unforgettable. The Braves’ 1919 game with the Tigers was canceled when Dublin promoters insisted that Ty Cobb play in the game.

Nimbocumulus clouds rolling in from the west didn’t look so good for the game that day. But, that didn’t stop the fans from plunking down their hard earned, nearly pure silver coins for a fine bench seat or staking out a good spot along the fence.

Promoters of the game in Dodge County set out to improve their fairgrounds by laying out a permanent athletic field inside of the existing horse racing track. The planners, in anticipation of the newest sensation of the day, designed the field to accommodate the landing of the highly popular biplanes, which entertained old and young alike.

To maximize the fan’s view of the game, home plate was situated directly in front of the grandstand, which was divided into sections to optimize ticket prices. In the days and weeks leading up to the game, ticket sales, mainly held in three local drug stores as well as locations in other cities, were exceptionally brisk. Advertisements boldly proclaimed, "There is going to be a real, jam up, honest to goodness ball game with real, sure enough major league players."

The teams, with a squad of sportswriters and photographers tagging along, were scheduled to arrive in five Pullman rail cars at 1:45 p.m. on the afternoon of March 26, 1920. The game’s first pitch was set for 3:00 p.m. sharp. Onto the field they came, real major league ball players. Eight thousand hands clapped. Four thousand mouths cheered. It was time to play ball!

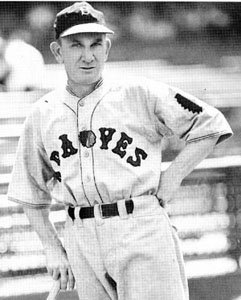

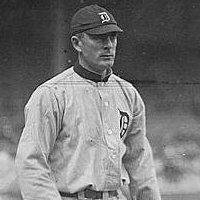

The Detroit Tigers were led by the legendary Ty Cobb. Surviving newspaper accounts of the day never revealed whether or not Cobb was in uniform that day, but he was with the team and ready to play. Bengal manager Hughie Jennings - himself a future member of the Baseball Hall of Fame - was tired of being drubbed by the Beaneaters from Boston. So, instead of trying to make do with a make shift lineup, Jennings sent his line up card out to umpire Finneran with his best players pencilled in. The Tiger lineup featured Harry Heilmann playing at first base. Heilmann, a four-time American League Batting Champion, was consistently among the league leaders in offense and defense. Named to the Hall of Fame in 1952, "Slug" Heilmann is still regarded as one of the top players of the 20 th Century.

Six years earlier in 1914, they called Braves’ manager George Stallings’ team, "The Miracle Braves," for their miraculous climb from the National League cellar on July 18 to a World Championship with their four-game sweep of the seemingly invincible Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. Stallings, a resident of Jones County, was the first to make Georgia the home of the Braves, when he brought them to Macon, Columbus, and sometimes even to his own home in Jones County for spring training.

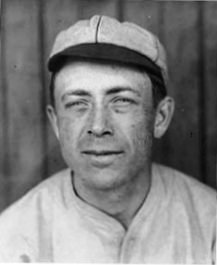

Playing at shortstop for the Braves was Walter "Rabbitt" Maranville, a consistent fielder who retired as the all time positional leader at shortstop in put outs. Also present, but playing little for the Braves that year, was Hank Gowdy. Gowdy, who went on to play 21 seasons, played for the "Miracle Braves" and was forever known as the first major leaguer to enlist in the Army in World War I. Known more for his glove than his bat, Gowdy lost many bids for election to the Hall of Fame.

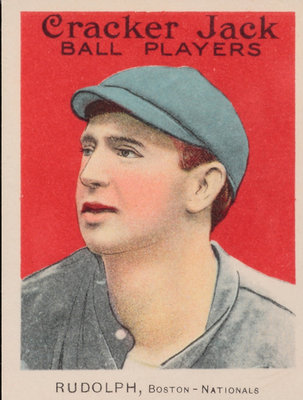

Manager Jennings sent George "Hooks" Dauss to the mound in an effort to prevent a fourth straight loss to their traveling mates. Dauss, whose 221 wins for the Tigers in 15 seasons is a franchise record, garnered 21 of his victories in the previous season. Stallings countered with his old reliable, Dick Rudolph. Rudolph, the sole remaining pitcher from the 1914 squad, started the first game of the 1914 World Series and baffled Connie Mack’s hapless Athletics with his elusive, and then legal, spitball pitches.

The Braves quickly appeared that they were going to run away with yet another game, jumping out to a two-unearned run lead in the bottom of the first inning. Dauss settled down. Going back to his 1919 form, the curveball ace held the Braves scoreless going into the top of the 4 th stanza.

Ralph "Pep" Young, exceedingly efficient at getting on base, led off the top of the 4 th for the Tigers with a base on balls. Sammy Hale, who hailed from Glen Rose, Texas, flied out. Bobby Veach, the all time Major League leader in putouts for a left fielder and the first Tiger player to ever hit for the cycle, doubled. Veach never stopped running. When a "dead duck" throw went wild, Veach followed Young home to tie the game at 2-2.

Dauss pitched one final inning until he was relieved by Ernie Alten in the 5 th . Alten, who shut out the Braves for the rest of game, had little luck in the regular season when posting a pathetic 9.00 ERA in his only year in the Majors.

In the top of the 6 th inning, Young once again led off, this time with a solid single. Sammy Hale, who led the AL in sacrifice hits that season, sacrificed himself, driving Young to second base. Not wanting a repeat of another Veach (2-3) hit, Boston pitcher, "Handsome Hugh" McQuillan, intentionally walked the Tiger outfielder, who stands alone in baseball trivia as the only player ever to pinch hit for Babe Ruth.

Harry Heilmann, who sported a lifetime batting average of .342 and who along with Ted Williams were the last two AL batters to post a .400 plus batting average, disappointingly flied out. With two runners on and two outs in the inning, Babe Ellison, whose best playing days were ahead of him as a great player in the Pacific Coast League, doubled, driving in both Hale and Veach and sending the Tigers to a 4-2 lead, a margin which they would hold until the end of the contest.

Alas, the game came to an end. The exhilarated crowd scattered into the countryside. The Braves’ streak was over. The teams met in Macon on Saturday and again in Atlanta on Sunday. Both teams finished next to dead last in their respective leagues, each more than 30 games out first place. Ty Cobb, in the twilight of iconic career, suffered a leg injury and missed 40 games that year. It would the last of George "The Miracle Man" Stallings’ 14 seasons at the helm of a major league team.

All of that was lost on those four thousand fortunate baseball fans, who for the most part, saw their first and only major league game on that March day when giants played on their field.

Seaborn Tipton should have known better. After all, he was a duly deputized constable of the Bailey Militia District of Laurens County. But, on a warm winter night a century and a quarter ago, Seaborn Tipton did a bad, bad thing. He conspired with a young friend Joe Weaver to rob old man Joseph Perry.

Joe Weaver, a seemingly chronic scoundrel, had been in trouble before. Earlier that winter, Weaver, Charley Jackson, and Fed Hightower robbed the business house of J.T. Smith. The teenager Weaver made his way over to Meriwether County, where he ironically served as a night guard of a convict gang. When a letter to Fed Hightower revealed Weaver’s location, W.C. Thompson was dispatched to return the fleeing felon back to Laurens County and justice.

Weaver was convicted of the burglary and sentenced to fifteen years in the state penitentiary. But, before serving very little of his sentence, young Joe surreptitiously secured a two-inch auger, bored through an exterior jail wall, and fled into the darkness. The convict didn’t stray too far from his home, hiding in the woods near the home of his good friend, Seaborn Tipton. Tipton’s wife, the former Miss Amanda Wynn of Wilkinson County, would later admit that her husband "was feeding someone in the woods for some time."

Weaver, a tall, handsome, curly haired, blue eyed, light complected teenager with pretty, white teeth was desperate to get enough money to allow him to flee from Laurens County and take up a new life far, far away. Weaver and his father, Seaborn L. Weaver, joined Tipton to discuss a plot to murder Joe Perry, who had married a sister of S.L. Weaver’s wife. The men knew Perry kept money around his house. Perry, a well-respected man in his community, was a seventy-three old veteran of the Civil War. Perry, too old to actually serve in the infantry, joined the local militia at the age of fifty.

On the night of March 11, 1887, Joe Weaver and Seaborn Tipton set out in the dark to rob their neighbor Perry, who lived some four to five miles north of Dublin. Tipton draped a red calico dress over his head. Mrs. Tipton, his willing accomplice, cut out spaces for his eyes, nose and mouth. The daring duo crept up to Weaver’s modest abode, illuminated by a bright waning gibbous, midnight moon.

The perfidious pair picked up a fence rail and used it as a battering ram to break down in the bedroom door of the slumbering victim. As the intruders entered Perry’s bedroom, Perry sprang up from his bed as fast as a septuagenarian possibly could. Weaver and Tipton grabbed and wrestled with Perry, who was finally able to pull of his arms free.

One attacker grabbed Perry’s free arm and yelled, "Shoot him! Shoot him!" A single shot rang out. The attackers fled into the moonlight. Perry reached for his gun and fired in the direction of his assailant’s flight. Two ineffective shots were returned in Perry’s direction. One attacker, shot through the heart by the other attacker, staggered into Perry’s yard and fell dead on the ground. Thinking that his attackers had fled in frustration, Perry, overwhelmed with the excitement, laid back down and went to sleep.

The following morning, a young Negro boy went out to Perry’s well to draw a bucket of fresh well water. The boy found a dead man, which he assumed to another Negro. While the coroner was sent for, the corpse was left lying where it fell until the constable arrived. When the coroner did arrive, he discovered that the dead body was indeed the body of Constable Tipton.

A general alarm of excitement and disbelief spread throughout the Bailey District. Marshal Martin and his blood hounds were summoned. An immediate reward of one hundred dollars was issued for the arrest of Weaver. Governor John B. Gordon, Georgia’s hero of the Confederacy, offered another $150.00 to brought the total bounty for the killer to $250.00. The possibility of lynching Weaver was quite real if he had been captured immediately. Law officials suspected that Weaver had already fled the county with less than $20.00 on his person.

Laurens County Sheriff J.C. Scarborough set out on Weaver’s elusive trail which led him to the home of Andrew Hobbs. At first, Hobbs denied the sheriff permission to search his premises. Scarborough pressed the issue. After Hobbs, a well-respected county official, consented to a search, the Sheriff found Weaver’s hiding place in Hobbs’ gin house, complete with Weaver’s clothes, bedding, and personal papers. After the initial investigation, Justice K.H. Walker issued a warrant for A.J. Hobbs, Seaborn Weaver, and Ben Raffield for harboring the suspected murderer.

The intense manhunt continued. From time to time, rumors of Weaver’s presence in the community spread like wild fires throughout the county. One somewhat credible report led law enforcement officials out to Lick Pond, a thicket so dense that naked eye visibility of any thing but trees was impossible beyond a few feet.

Sheriff Scarborough’s attempts to capture Weaver were exacerbated when in late June published reports in the Dublin Gazette said that Tipton, Weaver’s victim, was seen with his family, who followed him around the countryside, causing much calamity over Tipton’s return from the dead.

On April 1, The Sandersville Progress reported that Weaver was captured in Brewton. This report, like all the others of his sighting or capture, turned out to be false. An exhaustive search of surviving newspapers revealed no reports that Weaver was ever captured. Joseph Perry died on February 23, 1898.

His one deed of depravity done, his one irresistible impulse of avarice satisfied, his dreams of unwarranted wealth having slipped through his greedy hands, Seaborn Tipton, shot dead by a bullet shot from the gun of Joe Weaver, once again proved the ancient idiom, what goes around comes around.

Frances could remember the days when she wasn't free. Some seven decades after she received her freedom, she sat down in her home on Bridge Street in Athens with Sadie B. Hornsby to relate her memories of the days when she lived in one room log cabin with a stick and mud chimney. Frances never forgot the day she was free to go were ever she wanted to, when she wanted to. This is her story, in her own words, a woman's story of slavery as she saw it. They are her words, written long ago in interpretation of her own simple dialect.

"I was born way off down in Twiggs County 'bout a mile from the town of Jeffersonville. My Pa and Ma was Otto and Sarah Rutherford," Frances recalled. There were nine children and parents living in a meager hut they called their home. "Our bedsteads was made out of rough planks and poles and some of 'em was nailed to de sides of de cabins," Frances remembered. The mattresses were stuffed with wheat straw while it was in season. "When dat was used up us got grass from de fields. Most any kind of hay was counted good 'nough to put in a slave's mattress," Mrs. Willingham said. "Dey let us mix some cotton wid de hay our pillows," she added.

In her four years of slavery, Frances was somewhat exempt from toiling in the fields. "Us chillun never done much but play 'round de house and yards wid de white chillun. I warn't but four years old when dey made us free," she reminisced.

Frances could still remember her grandmothers and aunts. "I remember once Grandma Suck, she wes my Ma's mammy, come to our house and stayed one or two days wid us. Daddy's Ma was named Puss." Both of her grandmothers were field hands, but her mother worked in the house carding and spinning threads. Her aunt Phoebe weaved the threads onto cloth and her Polly sewed the cloth into threads.

As a child, Frances never had any money. "Nobody never give slave chillun no money in dem times. I never had none 'til atter us had done been give our freedom." But, she did see the money that her master Elisha Jones had. " I used to see Old Marster countin' of it, but de slaves never did git none of dat money. "

Frances spoke somewhat highly of her master. " Our Old Marster was a pow'ful rich man, and he sho' b'lieved in givin' us plenty to eat. It warn't nothin' fine, but it was good plain eatin' what filled you up and kept you well. Dere was cornbread and meat, greens of all sorts, 'taters, roas'en-ears and more other kinds of veg'tables dan I could call up all day. Marster had one big old gyarden whar he kept most evything a-growin' 'cept cabbages and 'matoes. He said dem things warn't fittin' for nobody to eat."

Jones trusted Otto enough to let him go hunting on his won. One delicacy in Frances' family was possum. Her family had to cook everything in an open fireplace. I've seen Ma clean many a 'possum in hot ashes. Den she scalded him and tuk out his innards. She par-boiled and den baked him and when she fetched him to de table wide a heap of sweet 'taters 'round him on de dish, dat was sho' somepin good to eat," Mrs. Willingham fondly recalled.

As a child slave, her clothes were at least decent. In summer, the girl slaves wore homespun dresses, with full skirts sewed tight to fit their waists and fastened down on their backs with buttons made out of cows and rams horns. "Our white petticoat slips and pantalettes was made on bodices. In winter us wore balmorals what had three stripes 'round de bottom, and over dem us had on long sleeved ap'ons what was long as de balmorals. Slave gals' pantalettes warn't ruffled and tucked and trimmed up wid lace and 'broidery lak Miss Polly's chilluns' was," Frances concluded.

The adult slaves on the Jones' plantation wore rough brogan. Frances and the other children wore the hand me down shoes that the Jones children had outgrown. "Dey called 'em Jackson shoes, 'cause dey was made wid a extra wide piece of leather sewed on de outside so as when you knocked your ankles 'gainst one another, it wouldn't wear no holes in your shoes. Our Sunday shoes warn't no different from what us wore evvyday," Frances said.

Elisha and Mary Jones were wealthy by most standards. In the year before the Civil War began, Jones owned $20,000 worth of real estate and $36,500.00 of personal property including slightly more than fifty slaves.

"Marse Lish Jones and his wife--she was Miss Polly--was our Marster and Mist'ess. Dey sho' did love to be good to us. Dey had five chillun of deir own, two gals and three boys. Dey was: Mary, Anna Della, Steve, John, and Bob. 'Bout deir house! Oh, Missus, dat was somepin to see for sho'.

Frances remembered the Jones's plantation house near the Town of Marion, then the capital of Twiggs County. "It was a big old fine two-story frame house wid a porch 'cross de front and 'round both sides. Dere was five rooms on de fust floor and three upstairs. It sho' did look grand a-settin' back dar in dat big old oak grove," the old slave woman looked back.

Mrs. Willingham vividly recalled her old master, "Old Master had a overseer but he never had no carriage driver 'cause he loved to drive for himself so good." Willingham said that she never saw her master do anything except drive his carriage, walk a little and eat all that he wanted to because he was rich man and didn't have to do anything. She recalled that the plantation was very large and although she couldn't remember just how many slaves lived and worked there, she did remark, "Dat old plantation was plumb full of 'em."

Field work was hard. ""Our overseer got all de slaves up 'fore break of day and dey had to be done et deir breakfast and in de field when de sun rise up," Willingham remembered. The slaves would work all day past twilight before they came back to their quarters to eat supper and rest.

Whippings on the Jones place were somewhat rare, at least Frances never saw one. She did remember the dime when she climbed on top of the porch of the big house and flapped her arms and crowed like a rooster. " Dey told me to come on down, but I wouldn't mind nobody and kept on a-crowin' and a-flappin', so dey whupped me down," Willingham remarked.

Frances and the other slaves, although a few miles from the nearest battle at Griswoldville, saw the war coming to an end. Although she was barely four years old, she told her interviewers, "Mercy me! I'se seed plenty of dem yankees a-gwine and comin'. Dey come to our Marster's house and stole his good mules. Dey tuk what dey wanted of his meat, chickens, lard and syrup and den poured de rest of de syrup out on de ground.," Mrs. Willingham remembered.

Free from all the helpless despair of seemingly eternal bondage, Frances Willingham was no better off than she was before she was granted her freedom. She had little that she could truly call her own. Slaves had their freedom, but had little choice of where to go and how to scratch out a living. Many of the things the former slaves had provided for them were now gone or beyond the reach of their somewhat less than meager incomes would allow. Although legally free, many of the slaves remained on the plantations and continued to see their former masters as still their masters.

Education was almost nonexistent in those days for black children. "I ain't never been to school a day in my life, 'cause when I was little, black children weren't allowed to read and write," she remembered.

Going to church was different too. Before the war, slaves and their masters worshiped in the same church. After the war, congregations were ironically segregated. "Colored folks had their own church in a settlement called John the Baptist," Willingham remembered in recalling that she and the other children loved going to baptisms. "Day took dem converts to a hole in de crick what day had got ready for dat purpose. De preacher went fust, and den he called for de converts to come on in and have deir sins washed away," she said.

Funerals were primitive as well. Willingham explained that Elijah Jones had set apart a burying ground for his slaves adjoining his own family's cemetery. "Us didn't know nothin' 'bout no fun'rals. When one of de slaves died, dey was put in unpainted home-made coffins and tuk to de graveyard whar de grave had done been dug. Dey put 'em in dar and kivvered 'em up and dat was all dey done 'bout it," Willingham recalled.

Frances reminisced about a single wedding on her master's plantation. She never forgot the day when Miss Polly gave her one of little Miss Mary's dresses to wear to the wedding. "Only dey never had no real weddin'. Dey was jus' married in de yard by de colored preacher and dat was all dere was to it," she recollected.

Frances Willingham fondly recalled Christmas times in her youth. She remembered going to bed early because she and the other children were afraid that Santa Claus wouldn't come to see them. "Us carried our stockin's up to de big house to hang 'em up. Next mornin' us found 'em full of all sorts of good things, 'cept oranges. I never seed nary a orange 'til I was a big gal," she reminisced.

Food was plentiful in holiday times. "Miss Polly had fresh meat, cake, syrup puddin' and plenty of good sweet butter what she 'lowanced out to her slaves at Christmas. Old Marster, he made syrup by de barrel. Plenty of apples and nuts and groundpeas was raised right dar on de plantation. In de Christmas, de only work slaves done was jus' piddlin' 'round de house and yards, cuttin' wood, rakin' leaves, lookin' atter de stock, waitin' on de white folks and little chores lak dat," she remembered. Hard work resumed on the day after New Year's Day.

Medical care, although primitive at best, was available, if only on a limited basis. Of those days, Willingham recalled, "White folks was mighty good and kind when deir slaves got sick. Old Marster sont for Dr. 'Pree (DuPree) and when he couldn't git him, he got Dr. Brown. He made us swallow bitter tastin' powders what he had done mixed up in water. Miss Polly made us drink tea made out of Jerusalem oak weeds. She biled dem weeds and sweetened de tea wid syrup. Dat was good for stomach trouble, and us wore elder roots strung 'round our necks to keep off ailments," Mrs. Frances remarked.

The women of Frances Willingham's day had little rest, even after leaving the fields. She recalled that when the slaves came in from the field, the women cleaned the houses after they eat and washed clothes early in the morning so that they would be dry for the next day. She remembered that the grown men would eat, sit around and talk to other men and then go to bed.

Saturday nights were a time to frolic. Quitting time came around three or four o'clock in the afternoon. "Sadday nights de young folks got together to have deir fun. Dey danced, frolicked, drunk likker, and de lak of dat. Old Marster warn't too hard on 'em no time, but he jus' let 'em have dat night to frolic. On Sunday he give dem what wanted 'em passes to go to church and visit 'round," she reminisced.

Jones allowed his workers little rest from the time crops were planted until they were harvested. "My master did allow us slaves to have cornshuckin's, cornshellin's, cotton pickin's, and quiltin's," said Mrs. Willingham. Jones's groves of pecan, chestnut, walnuts and other trees were lucrative . When all the nuts were gathered, Jones sold them to the rich people in the cities. Afterwards, he gave his slaves a big feast with plenty to drink. After a long celebration, Jones allowed the slaves a few days to recover before resuming their grueling duties.

In her final years, Frances Willingham reflected on her freedom, "Me, I's so' glad Mr. Lincoln sot us free." She believed that if she was still a slave, that she work just the same, sick or not. "Now I don't have to ax nobody what I kin do. Dat's why I's glad I's free," Willingham concluded.

After leaving the Jones plantation, Frances moved to Putnam County, Georgia, where she married Green Willingham, of neighboring Jasper County. "I didn't have no weddin'. Ma jus' cooked a chicken for us, and I was married in a white dress. De waist had ruffles 'round de neck and sleeves," she said as she looked back to her wedding day.

Frances Willingham lived a long life. She worked hard to provide for her seven boys and ten girls. Then as she got older she did all she could to look after her 19 grandchildren and 21 great grandchildren.

In this month of March when we celebrate Women's History Month, let us look back and reflect on all the Frances Willinghams of the world, who toiled and worked with little rest to provide for their families as best as they could.

Greek Versus Greek

Two metallic behemoths clashed in the water of Hampton Roads, Virginia, one hundred and fifty years ago this week. One Wilkinson County man was there. What followed was the first naval engagement between two ironclad warships, the U.S.S. Monitor and C.S.S. Virginia, a converted frigate formerly dubbed the Merrimac by its Northern builders.

Ellsberry Valentine White was born in Wilkinson County, Georgia in 1839. By adulthood, he had moved to Macon and later to Columbus, Georgia. At the outbreak of the Civil War, White was working as a store clerk in Columbus and living in his mother's boarding house.

On April 20, 1861, some ten days after the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, White joined the City Light Guards, designated as Co. A, 2nd Battalion, Georgia Volunteer Infantry. The members of the company elected him as 2nd Sergeant. Sgt. White would transfer to the Confederate Navy near the end of November.

White's regiment was stationed near Portsmouth, Virginia. He expressed an interest in working on the refitting of the U.S.S. Merrimac and was accepted into the naval service on January 18, 1862 and commissioned as the Jr 3rd Engineer in charge of the speaking tube and the gong on the deck of the ship. It was White's job to convey orders from the officers in charge back to the engine room.

The Virginia's builders covered the Merrimac's hull with 20-inch thick heart pine boards, overlaid with four- inch-thick oak planks. Two-inch-thick by seven-inch-wide metal strips were alternately laid horizontally and vertically were place on the exterior of the wooden hull. Her builders and crew believed she would be invincible and that with her dominance of the water ways leading inland from the Virginia coast up the James River, Richmond would be impervious to bombardment by Union naval ships.

Engineer White recalled, "Finally the great ship was reported ready for duty, and well do I remember the words that fell from the lips of our commander, Commodore Buchanan. He told us not to mistrust him; that he intended to do his duty, and expected the same from one and all on board." On midday of a calm, clear, bright Saturday on March 7, 1862, with a gentle breeze coming out the north-north-west and a slight ebb tide on the Elizabeth River, the CSS Virginia cast off from her moorings at the Navy yard on her maiden voyage.

The ship headed for Newport News, where she found the U.S. S. Cumberland and U. S. Congress lay at anchor, blockading the James River. The Union ships opened fire first and then every Federal gun within range of the Virginia joined in the enfilading of the ironclad, which reserved her heavy guns until the last moment to take maximum effect on the wooden warships.

"The Virginia's bow rifle was used with terrible effect; and, as he been frequently stated, opened a hole in the Cumberland large enough for a horse and cart to drive through. We made directly for the later vessel. When at probably fifty yards distance, with slackened speed, but with determined purpose, we moved on toward the gallant ship, and struck her the deadly blow," White wrote in his 1906 account of the battle.

"With probably one hundred guns firing upon us from various points, we came within two hundred yards of the now grounded Congress, upon which we opened fire. After we had delivered several well-directed shots that sent disaster to that ship, and many souls to their eternal home, she (the Congress) hoisted the white flag, and all firing ceased. Arrangements were then commenced for receiving the surrender and removing the dead and wounded from both the enemy's ship and our own," White continued.

"Before we had grounded, the Monitor was discovered coming out from where the Minnesota lay aground, appearing to us, as she has been called, "a cheese-box," or a "tin can on a shingle," White recalled. Lookouts soon recognized the Ericsson Monitor and the Virginia's guns opened fire. "Straight on she came toward us, and when in good position let loose her heavy guns, giving us a good shaking up. Thus she continued circling around us, and every now and then throwing the heavy missiles against out sides. We, in response, as she passed around, brought every gun aboard our ship to bear upon her. It was now "Greek meeting Greek, iron against iron," Engineer White proclaimed.

"Never before had ships met carrying such heavy guns. From both vessels the firing was executed with great rapidity and with equal skill, with but little effect on either side. However, our weak points seemed to be known to the commander of the Monitor, and so well did we attack these, that soon on the starboard midship, she so bent in our plating that the massive oak timbers were cracked," White wrote in his harrowing account of the battle.

"Then, with a settled determination to run the Monitor down, as a last resort, seeing that our shots were ineffective, I was directed to convey to the engine room orders for every man to be at his post. We caught and did run into the Monitor, and came near running her under the water with our starboard bow, drove against her with a determination of sending her to the bottom, and so near did we come to accomplishing our object that from the ramming, White recollected." The victorious crew waited for the return of her beleaguered adversary. The crew of the victorious Virginia acknowledged the thundering saluting shouts of those who witnessed the tremendous triumph from the shores.

By late afternoon, the Virginia was back at the Navy Yard. "The grand old ship was a picture to behold. You could hardly put your hand on a spot on the sides, or smokestack, that had not been battered by the shot of our enemy," White remembered. After making badly needed major repairs, the Virginia was once again ready for action. With the fall of Yorktown and other Confederate fortifications along the lower James River, Flag Officer Josiah Tattnall, of Georgia, saw that the Virginia would not be able to travel upriver to safer positions toward Richmond. The ship was run aground above Craney Island.

"We had but two boats to land our large crew safely on shore; consequently we had to leave all our personal effects on board the steamer. I was one of ten selected to destroy the ship, and held the candle for Mr. Oliver, the gunner, to uncap the powder in the magazine to insure a quick explosion, and, necessarily, was among the last to leave her decks," the Confederate engineer sadly looked back.

"A more beautiful sight I never beheld than that great ship on fire, flames issuing from the port holes, through the gratings and smokestack-the conflagration was a sight ever to be remembered. Thus closed the life, on Saturday night, May 12, 1862, of our gallant ship," White lamented.

White resigned his commission later that summer and was transferred to duty aboard the C.S.S. Baltic in Mobile Bay. Nearer the end of the war, White rejoined the Infantry and participated in the battles in the defense of Atlanta.

Captain Ellsberry V. White returned to Portsmouth after the war where he worked in the hardware business for the rest of his life, which ended on February 28, 1919.

.

THE ROZAR BROTHERS

Pioneers On A Submarine

When Leonard and Albert Rozar spent the days of their youth working on their father's farm in the Burgamy District of northwestern Laurens County, they never dreamed that they would spend decades serving as stewards and mess attendants aboard submarines and in other positions in the United States Navy.

The Rozars grew up in a time when the number of black sailors serving aboard sailing ships was systematically restricted and when the number of black submariners was even more limited. All of that began to change in the years leading up to the beginning of World War II.

It was in those days before modern, nuclear powered submarines patrolled the waters of the oceans of the world when these two Laurens County brothers, "Big Rozar" and "Little Rozar" became pioneers of sorts. The Rozars set the standard for longevity of a duo of brothers with each serving for three decades in the United States Navy.

In his definitive work, Black Submariners in the United States Navy, 1940-1975, Glynn A. Knoblock interviewed scores of African-American sailors who served aboard submarines. Two of those sailors whom Knoblock interviewed were Leonard and Albert Rozar, of Laurens County, Georgia.

Leonard Cicero Rozar, the second son of Monroe Griffin Rozar and Mattie Rozar, was born on the second day of July 1917. After the fall crop of 1939 was harvested and the winds of war began to howl out of Europe, Leonard Rozar traveled to Macon in the week after Thanksgiving to enlist in the Navy of the United States. Rozar was quoted as saying "No army for me. I'd heard devious things about them."

Rozar reported for duty at Norfolk. After undergoing the usual military training exercises, Leonard was assigned to duty as Mess Attendant, Third Class. Black sailors had historically been relegated to menial duty as cooks, stewards, and laundrymen for the crew and officers aboard submarines. Nearly all of the other submarine crewmen were white. Ironically by serving in close quarters with other stewards and white crewmen, these cooks and servants developed closer bonds with their crew mates.

Rozar left for duty in Pearl Harbor on the day after Easter in 1940. His first assignment was aboard the U.S.S. Plunger and later the U.S.S. Pollack, on which he served for the remainder of the year. Rozar joined, as a Mess Attendant 1st Class, the crew of the newly commissioned, U.S.S. Tuna, on the second day of 1941. A year later, the Tuna set out for Pearl Harbor, a month after the Japanese attack on the island base. Rozar's boat set out to patrol the waters of the East China Sea until it was assigned to the waters around New Guinea later in the year, 1942.

"I was a qualified sound man aboard (the Tuna), and my battle station was in the forward battery. I was on the standby sound gear, and also in the control room, ready to pull the demolition plug if needed," Rozar recalled.

Just days before Christmas, Leonard transferred to the U.S.S. Saury, on which he would serve until the last day of 1944. During his two years aboard the Saury, the sub saw little action except bad weather and broken equipment. Rozar recalled that he enjoyed being aboard the Saury. It was years later when he discovered that fellow Steward's Mate 1st Class, William Henry Cosby, was the father of actor Bill Cosby.

Rozar was promoted to Steward First Class and transferred to the U.S.S. Sailfish, which basically sat out the rest of the war in the Pacific, working instead as a training boat off the Atlantic coast of the United States.

Over the remainder of his 30-year career, Leonard Rozar served aboard the Sailfish, the Flying Fish, and the Chopper, before moving to New London, Connecticut in 1962. Rozar ended his career by serving as a Chief in Athens, Georgia, not far from home, and finally with a 20-month tour aboard the Cruiser Little Rock, an assignment which he did not care to have. In 1969, after three decades in the United States Navy, Leonard Rozar retired as a Senior Chief Petty Officer, the second highest enlisted grade in the Navy.

Leonard Cicero Rozar died on March 31, 2008 in San Diego, California.

Albert Rozar, the third son of Monroe Griffin and Mattie Rozar, was born in 1919. A highly gifted athlete in high school, Albert followed in his brother's footsteps when he joined the Navy on August 14, 1941. After attending boot camp at Norfolk and machine gun school at Mare Island, Albert Rozar reported for duty at Pearl Harbor. On December 11, 1941, as a late addition to the crew of the U.S.S. Gudgeon, Albert Rozar rode aboard the boat in the first war patrol of a U.S. submarine in World War II.

A transfer to the Pargo gave Albert Rozar more opportunities to come out of the galley for duty as telephone operator in the forward battery and when on the deck, the opportunity to man the 40mm guns. On his first patrol aboard the Pargo in the late fall of 1943, Rozar's boat was a part of only the second wolfpack operation by U.S. submarines. He remained aboard the Pargo, which sunk six ships, until the fall of 1944.

After leaving the Pargo, Albert Rozar was assigned to the staff of Commodore Charles "Weary" Wilkins on Midway. When the war was over, Albert was transferred to New London, Connecticut. In 1946, Albert reported for duty aboard the U.S.S. Segundo. Another year meant another assignment. In 1947, Rozar served aboard the U.S.S. Greenfish, which was one of the first submarines to receive personnel via helicopter from an aircraft carrier.

During the 1950s, Albert served aboard the Cobbler, the Shark, and the Orion. He equaled his brother's tenure in 1971, retiring as a Senior Chief Petty Officer.

The careers of Leonard and Albert Rozar spanned five different decades, three wars, and totaled sixty years of service in the United States Navy. They saw the roles of African-American sailors aboard submarines go from mess attendants and stewards aboard untested, relatively primitive submarines to respected positions as Senior Chief Petty officers and commissioned officers in the modern nuclear navy.

Missed Chances and Broken Dreams

When he was 12, Quincy Trouppe used to hang out on Compton and Market Streets in St. Louis. He dreamed about the lucky days when he would race down the street and snatch up a ball flying out of Stars Park, where the St. Louis Stars of the old Negro leagues played. He redeemed those balls for tickets into the stadium to see his heroes play. It was his dream that one day he would be on that very diamond and other diamonds like it around the country. More than twenty years would elapse before black men would be allowed to play Major League Baseball. And, Quincy Trouppe was one of the first.

It was in the fading twilight of his illustrious baseball career that this Dublin man rose to the top of the game as the first African American catcher in the American League. But, all too soon, his life long dream turned into a disheartening nightmare when he was rejected by the game he loved so much.

Quincy Trouppe was born on December 25, 1912 in Dublin, Georgia. His family moved to St. Louis, Missouri before he reached the age of ten. At the age of 18, Quincy Trouppe realized his dream and began his professional baseball career with the St. Louis Stars in 1931. Over the next twenty seasons, Trouppe starred with the Homestead Grays, Kansas City Monarchs, and the Cleveland Buckeyes as well as a host of other teams in his eight seasons in the Mexican League.

Trouppe starred for the West team in five all-star games, four as a catcher from 1945 through 48. He managed the Buckeyes to Negro American League titles in 1945 and 1947 and one World Championship in 1945. After the 1936 season, Trouppe took off a year from baseball to box, having won a major heavyweight tournament title in 1936.

It was in October 1951 after returning from Mexico when Quincey got a call, one which would change his life forever, or so he thought. A bellboy in a hotel lobby in Caracas, Venezuela called Trouppe to the phone. On the other end of the line was Hank Greenberg, a former Detroit Tiger home run champion and a future member of the Baseball Hall of Fame. Greenberg, a member of the front office of the Cleveland Indians, invited Quincy, who had another outstanding season in the Winter Leagues, to attend training camp with the Indians in the spring of 1952, sixty years ago this month.

"I was out of words," Quincy recalled in his autobiography, Twenty Years Too Soon. Greenberg offered Trouppe a minor league contract in Indianapolis But with the surprise proposal came an opportunity to make the big league team. It was the chance that Quincy Trouppe had been waiting for twenty years.

Excited to be in the big leagues, Quincy considered that he was in his best shape in many years. "No one who has ever broken into organized ball could have felt better than I did when I inked my name to that new Cleveland Indians contract," Trouppe wrote a quarter of a century later.

During spring training, Trouppe caught every third game and outhit the other two catchers, two to one. "I caught Early Wynn," a Hall of Fame pitcher, "for seventeen straight scoreless innings," he recalled. Trouppe also caught Hall of Famers, Bob Lemon and Bob Feller. Feller was considered as one of the greatest right-handed pitchers in baseball history.

In 1952, during the sunset of his career, Feller was beginning to struggle. Trouppe suggested to Indian fast baller that he develop a good change up and mix up his pitches. "I suggested this to Bob, and he pitched a shut out," said Trouppe, who never forgot the next day when Feller came up to him before the next game and said, "Quincy, you called a very good game yesterday. You used excellent judgment on the hitters, and you also knew how to use my most effective pitch. Keep up the good work."

It was on the last day of April 1952 at Shibe Park, home of the Philadelphia Athletics, when Quincy, wearing number 16 on the back of his gray flannel road uniform, played in his first game. At the age of 39 years, four months and five days, Quincey Trouppe became one of the oldest rookies in the history of baseball, a mark surpassed only by a scant few other older former Negro League stars.

Three days later at Griffith Stadium on a cool mid-spring Saturday in Washington, D.C., Quincy was catching when Indian manager Al Lopez, also a member of the Hall of Fame, called to the bullpen and signaled for Sam "Toothpick" Jones, Quincy's old Cleveland Buckeye teammate to come in to pitch in relief. Jones came into the game with one out trying to hold the Senators to a 5-4 lead.

Whether anyone among the 10,257 paid fans in the crowd noticed it or not, with Jones' first pitch to Senator's outfielder, Sam Mele, Quincy Trouppe and Sam Jones became the first black battery in American League history. The historic event seemingly went unnoticed in the sports pages across the country. Several years earlier, Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe, of the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League, became the first black battery in Major League history.

The American League record book was amended when the Indians tied an American League record when they used twenty-three players in a nine-inning game. After the game, Mele, who would pilot the Minnesota Twins to the 1965 American League Championship, was traded to the Chicago White Sox.

Trouppe was used sparingly, catching behind veteran Birdie Tebbetts, some six weeks older than Quincy and the decade younger catcher, Jim Hegan.

May 10, 1952 was a bittersweet day for Quincy Trouppe. For the first time in his major league career, Quincy Trouppe was a starting catcher in the major leagues. To make the game sweeter, Trouppe was playing against the Browns from his home in St. Louis. Early Wynn was pitching for the Indians, Tommy Byrne, a former Yankee star pitcher, for the visiting Browns.

Quincy came up to bat in the bottom of the third inning. He stroked his first Major League hit, a solid single to left, and scored his first major league run on Bobby Avila's single. It would be his last major league hit and his last major league run. It would be his last game in the major leagues.

In his ten-game stint with the Indians, Quincy, who got few opportunities to hit, posted a dismal .100 batting average, well below his .280 plus career average. Behind the plate, Quincy was as effective as ever, handling 25 chances without a single error and leaving the game of with a perfect major league fielding percentage.

While Quincy was working out the next day, he got a message to report to Greenberg in Manager Lopez's office. The news wasn't good. He was being demoted down to the farm team in Indianapolis. "This hit with such a force that I was speechless for a few minutes," Trouppe remembered. The veteran catcher spoke up in his defense that he felt he was being mistreated. Greenberg merely responded that the Indians felt that with him, they had no record to go on.

Quincy Trouppe became even more upset. During his 21 seasons in professional baseball, Trouppe had proven that he was one of the best catchers in Negro League history. He possessed a proven record of working with younger players and the game's greatest players as well.

Trouppe had caught some of the greatest pitchers in the game, including the legendary Satchel Paige and Dizzy Dean. He was once a roommate of Hall of Famer, Monte Irvin. Quincy played with and against many of the greatest players in the Negro League and baseball, period. His National League counterpart, Roy Campanella, had recommended him to the Indians.

Quincy Trouppe finished his career in Indianapolis before returning to St. Louis for a new life with his new wife, Myralin. Before the beginning of the 1953 season, the St. Louis Cardinals hired Quincy as a scout. Trouppe scoured the country for the best and most promising players.

Very quickly, he identified two outstanding young hitters and fielders. He began talking to the youngsters about signing with his team. Both were amenable and agreed to sign. But, when Trouppe presented his recommendations to the Cards' management, he was told not to offer the young men any contracts. The two men signed with other teams, one with Pittsburgh and the other with the Cubs. They were Roberto Clemente and Ernie Banks, two of the game's all time greatest players.

So you see this former Dublin man, who many regard as one of the best catchers in the history of the Negro Leagues, was denied the chance he so richly deserved. Nor was he ever praised by his team for his best two scouting recommendations, ones which were systematically rejected by his supervisors.

Despite the broken dreams and the missed opportunities, it was in the old days, his days, during the Golden Age of Baseball, when Quincey Trouppe, of Dublin, Georgia, was a shining star in a heaven of baseball greats.

They weren't exactly the weddings of the century, no one or two weddings are except to the couples themselves. But, when Dena Baum married Emanuel Dreyer and her sister, Blanche Alexandria Baum, took the hand of Junius Schiff in marriage, they were the largest weddings ever held in Laurens County. On this Valentine's Day, let's turn back the clock more than a century of ago and took a look at what truly glamorous weddings used to be about.

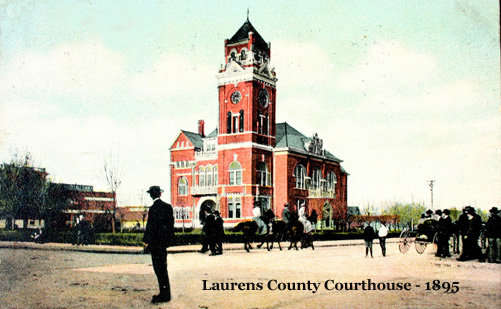

Dena Baum was the first of the daughters of Napoleon Bonaparte Baum and Louise Kohn Baum to get married in Dublin. Being of the Jewish faith, there were no synagogues in Dublin for the Baum girls to get married in. Misses Baum chose the secular venue of the Laurens County Courthouse. The brides' father was one of the city's leading merchants and public-spirited citizens at the turn of the 20th Century. Their mother was a Washington, D.C. socialite of sorts. Her father, Phillip Kohn, was once the architect of the Capitol. Mrs. Baum was in attendance at Ford's Theater on the night when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

It was a warm night on the 7th of January in 1903. Nearly 800 guests from around the city and around the state were filing into the courthouse hoping to get a good seat in the crowded courtroom. For the first time in the history of the county a couple would be married according to the rites of the Jewish religion. Newspaper writers billed it as "the largest ever witnessed in this section of Georgia."

The courtroom was elegantly decorated with evergreen and flowers as to disguise the normal use of the auditorium. A canopy, draped with sheer white cloth and bamboo vines, was erected in front of the judge's bench.

To get the guests into the mood, Professor Carl Leake led his orchestra featuring musical selections from the opera, "Martha." Mrs. T.H. Smith, Mrs. Carl Leake, S.M. Gibson and C.H. Kittrell sang the wedding march as the bridal party approached Rabbi Isaac C. Marcuson and the groom, Emanuel Dreyer, the junior partner of the successful retail grocery firm of Brandon and Dreyer, and his best man, Morriel Elkins.

Dena's younger sisters, Jeanette and Helen, served as ribbon girls. Adeline Baum, the maid of honor, preceded the bride and their father down the aisle to join the ushers dressed in tuxedos and the attendants, beautifully attired in satin dresses.

The beautiful and impressive, yet longer than usual ceremony, lasted well into the late hours of the evening. After the nuptials, the couple, the wedding party and their guests walked across the courthouse lawn to the Baum house on the northeast corner of the square.

After a wonderful honeymoon in Florida, the Dreyers returned to Dublin, all the more wealthy than when they left. With hundreds of gifts in hand along with a reported thousand dollars in gold, the Dreyers were ready to begin their dream life.

A more traditional June wedding took place at the courthouse on June 12, 1907. It was a perfect late spring day with fair skies and an ideal room temperature at 9:00 in the evening. Once again, there was an overflow crowd of friends and family pressed into the Laurens County courtroom. This time, the groom, Junius Schiff, was not as well known, but was fortuitously brought to Dublin to take a position as the floor manager of the Sam Weischelbaum Company, in which the Baum family held an interest.

Following the plans of her sister's wedding, an orchestra of family friends were on hand to play as the bridal party came down the aisle. For all of you wedding planners, a reporter described the auditorium, "From the door to the altar was laid with white crash cloth. A profusion of cut flowers, palms, ferns and pot plants was used in the decoration. The stand in back of the altar was draped with white ribbon and ferns, and on each were suspended the letter 'B' and 'S." Between the letters was a large heart made of ferns and cut flowers. Two large arches spanned the entrance. These were draped with white ribbon and ferns. From the altar was suspended a canopy studded with lights and draped with white ribbon and cut flowers. From this canopy over the bride and groom was suspended a large bell made of red and white roses.

Just as she had before, sister Adeline Baum, gowned in a lace robe and who would never marry herself, served as the maid of honor. Leo Weiss was the groom's best man. The groomsmen wore continental evening suits, while the bride's maids wore white lingerie chiffon dresses and carried white flowers.

After Rabbi David Marx of Atlanta presented the newlyweds, they walked out of the auditorium to the traditional Mendelssohn's Wedding March. Following the ceremony, another lavish reception was held in the Baum home across the square.

And just like it was before, wedding gifts filled the Baum residence. There was enough cut glass, dishes, silverware and serving pieces to entertain party guests for a lifetime. The Schiff's left her home at 2:00 in the morning to catch an afternoon train from Tennille to Savannah. The couple traveled to Norfolk, Virginia where they saw the sights around Old Point Comfort, Hampton, and Portsmouth. They left the Old Dominion and traveled to New York City, where after a short visit, traveled up the Hudson River to Niagra Falls, a common honeymoon destination of the day and in Dena's words, "the prettiest sight we saw." On their return home, the Schiffs toured Philadelphia, Washington and visited with the groom's parents in Atlanta before returning home after their twenty-five-day honeymoon tour. They would enjoy a marriage of fifty-five years.

Junius Schiff died on February 17, 1963. Dena died on May 12, 1972. Tragically, Emanuel Dreyer took his own life on May 29, 1923. Dena died on March 15, 1947. They are buried in the family plot in Section W of Northview Cemetery in Dublin.

Over the last century, weddings have changed dramatically. In some cases, they haven't changed at all. So, on this Valentine's Day, let me wish a happy life to all of those who love and who are loved by someone. Treasure all the days you have after you say your vows. In the case of the Baum sisters, one marriage lasted a lifetime while the other was tragically cut short.

The Littlest Giant

For forty years in the middle of the 19th Century in Georgia, Alexander Hamilton Stephens towered over most of his political colleagues in the Empire State of the South. Weighing between ninety and a hundred pounds, the frequently frail, regularly sickly, five-foot, seven-inch-tall leviathan served more terms than any other Georgian in the Congress during the 1800s. Although a proponent of slavery, Stephens fought hard to keep his native state in the Union. When all of his efforts failed, Alexander Stephens, Laurens County's first Congressman, accepted the nomination as Vice-President of the Confederate States of America.

Alexander Stephens was born on February 11, 1812 near the town of Crawfordville in Taliaferro County, Georgia to his parents Andrew Stephens and Margaret Grier Stephens. After losing his mother as an infant, Alex suffered the loss of both his father and stepmother in 1826. With no family to raise him, Alex was blessed to be taken in by the Rev. Alexander Hamilton Webster. Stephens changed his middle name to honor his counselor and mentor. Alex Stephens graduated with highest honors from the University of Georgia, where he was a roommate of Dr. Crawford W. Long, the discoverer of anesthesia. He taught school for a year and a half before his admission to the bar in 1834. Two years later, Stephens was elected to represent Taliaferro County in the Georgia Legislature, serving through 1841, when he was elected to represent his county in the Georgia Senate. In his relatively brief legal career, Stephens earned a reputation as a highly effective criminal defense lawyer.

A member of the southern branch of the Whig Party, Stephens was elected to fill the unexpired term of Congressman Mark Cooper in 1843. The following year, Georgia adopted a new system of Congressional Districts which replaced the at-large system. Stephens was elected to the 7th Congressional District of Georgia, which covered an area composed of Baldwin, Greene, Hancock, Laurens, Morgan, Oglethorpe, Putnam, Taliaferro, and Washington counties. Stephens served on the Committee of Twenty- One to ensure the election of Whig candidates along with Winfield Wright of Laurens County.

Congressman Stephens, whose Unionists' views made him popular with local voters, continued to represent Laurens County until congressional districts were redistricted in 1852. After rifts developed between northern and southern members of the Whig Party, Toombs, Stephens and Douglas left the party in the early 1850s to form a new party, the Constitutional Union Party. Stephens, then a full-fledged Democrat, was a strong supporter of President James Buchanan and served as a presidential elector for Stephen Douglas, seen as a traitor by many in the South, in the 1860 election.

Stephens, who served in Congress until 1859, was not the strongest advocate of slavery in his early years, although his best friend, Robert Toombs, was. As the winds of war began to howl in 1860, Stephens was elected to attend the Secession Convention held in Milledgeville in January 1861. He desperately implored the delegates to cast their ballots in favor of Georgia's remaining in the Union in an attempt to save her from what he foresaw as her inevitable destruction. Although opposed to Abraham Lincoln's policies, Stephens knew that the Republicans, who had just come onto the national scene, did not possess the requisite number of votes to adopt Lincoln's policies into law.

Despite his desperate struggles to keep Georgia as a part of the United States, Alexander Stephens accepted his nomination to serve in the Confederate Congress. On his forty-ninth birthday, Congressman Stephens was sworn in as the first and only Vice-President of the Confederate States of America.

Alexander Stephens took a more cautious approach to prosecuting a war against the North. Stephens favored delaying offensive actions in order to build up and train Southern forces. During the second year of the war, Stephens first began to reveal his differences with those of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Stephen's criticism of Davis's military strategies increased. So did his disdain for the Confederate president's policy of conscription and suspension of the constitutionally guaranteed right of habeas corpus, policies which were also adopted by Abraham Lincoln in the North. All the while, Stephens sought out ways to end the hostilities after the pivotal battle of Gettysburg.

Thirty-two days after Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Union forces arrested Stephens at his home, Liberty Hall, in Crawfordville. After serving five months in the prison at Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, Stephens returned to Georgia. Elected to the United States Senate from Georgia in 1866, Stephens was denied his seat as Georgia had not formally returned to the Union.

After the virtual end of Reconstruction, Stephens filled the unexpired term of Ambrose R. Wright in the United States Congress. Stephens won reelection for four more terms bringing his total service in the Congress to twenty-six years, a record only matched in the 20th Century by Carl Vinson, Paul Brown, John Lewis and Edward Cox.

At the age of seventy, Stephens resigned his seat in Congress following his election as the 50th Governor of Georgia. On March 4, 1883, some four months after his election, the ailing scion of Georgia politics passed away in his home.

Alexander Hamilton Stephens made few reported appearances in Dublin and Laurens County. The little man, with a shrill voice and a highly intelligent mind, made at least one stop in the county during his travels across the state. Stephens accepted the invitation of Ira Stanley, who invited the traveler into his home. According to Stanley family tradition, when the men were discussing Stanley's desire to build a new home in the northern tip of Laurens County, Stephens called for a pen and paper and sketched out a design of his own home. Stanley reproduced his elegant home, near Chappell's Mill, in close conformance with Stephen's drawing.

It has been said that Alexander Stephens had a desire to help those less fortunate than himself. His home was frequently open to all travelers, rich or poor. More than one hundred students, of both races and both sexes, were said to have benefitted from his generous private scholarships.

Like Thomas Jefferson, another great American of the same ilk, Alexander Hamilton Stephens died with little or no assets, other than the infinite number of friends and a long legacy of service to our state and our nation. And, it was in this week, two hundred years ago, that the "littlest giant" in our state's political history was born.

The War Years

On this day in 1764 in the British colony of North Carolina was born a general. Although he was widely heralded as an Indian fighter and brigade commander of the War of 1812, General David Blackshear of Laurens County rarely led his men into battle. Blackshear had seen war all too closely, watching his oldest brother James being killed by Tories during the American Revolution. This is the story of General David Blackshear, the soldier, planter, surveyor, and public servant during the years of the War of 1812.

Known to many as "The Second American Revolution," the War of 1812 began with a declaration of war by President James Madison on June 18, 1812 following a ten-year series of skirmishes at frontier outposts, impressment of sailors on the seas, and blockades of shipping. It was on the 4th of July in 1812, some three dozen years after America first declared its independence from the King of England that soldiers of the Georgia militia rendezvoused in Dublin to launch an attack on British fortifications in Florida, which would not become part of the United States until six years later.

During its regular session, the Georgia legislature on December 9, 1812, appointed David Blackshear to command the 2nd Brigade of the 5th Division of the state's militia. Dr. William Lee commanded the first division.

Blackshear's first known call to duty came in early August 1813, when Georgia governor David Mitchell wrote the general to move his brigade to the frontier and adopt measures to afford some security for the fearing inhabitants. Gen. Blackshear ordered Lt. Col. Ezekiel Wimberly to immediately man three forts: Twiggs, Telfair, and Jackson along the line of the frontier, then the Ocmulgee River. Blackshear ordered Col. Allen Tooke of Pulaski County and Major Cawthorn of Telfair to immediately do the same.

The General set out on a patrol to inspect the forts and reported back to the Governor, "I found the inhabitants in a high state of alarm - an immense number of whom had left and fled to the interior." Blackshear immediately began preparations to lay out an additional ten forts along the frontier, each manned by one subaltern, a sergeant, a corporal and fifteen privates and each approximately ten miles equidistant.

My mid-September, Gen. Blackshear reported that all threats of an eminent invasion had subsided, at least for the present. By mid-November, tensions along the Ocmulgee once again began to rise. Major General David Adams ordered Blackshear to send some of his best men to join a force of 157 men and to go out to the frontier to make improvements to existing fortifications and erect new ones and to report his activities to Major James Patton at Fort Hawkins.

On January 4, 1814, the newly elected Georgia governor Peter Early, a former judge of Laurens County Superior Court, replaced the ailing General John Floyd with his old friend, David Blackshear to command the army from Georgia in the lower Flint River region. Blackshear reported that a great number of his men were sick and that he needed substantial reinforcements to aid his 700-man force in guarding his forts and supplies, not to mention the effort to drive away the hostile Indians, all the Negroes, and the British forces at the mouth of Flint River.

Two years after the war began, Gov. Early reappointed Gen. Blackshear to command a brigade of first class militia along with Gen. Floyd. Blackshear responded, "Sir, I am at all times ready promptly to accept that or any other appointment you may think proper to confer on me in which it is in my power to serve my country."

Just as was the case in previous Septembers, tensions along the Georgia frontier began to explode. Blackshear ordered several units to move out from Hartford, opposite present day Hawkinsville. Adjutant General Daniel Newnan informed Blackshear that 2500 men would be needed to support General Andrew Jackson, then in the vicinity of Mobile. Several units from Blackshear's command were detached for that purpose.

Ten days before Christmas, Blackshear and his brigade received orders to move from their encampment at Camp Hope, two miles north of Fort Hawkins on the Milledgeville Road in present day Macon, to Hartford and then to open a road to the Flint River, where he was ordered to erect fortifications. No one in Georgia even realized that the war with Great Britain officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on Christmas Eve while Blackshear and his men were camping on the banks of the Ocmulgee.

Blackshear's men spent Christmas at Camp Blakely, two miles from present day Hawkinsville before moving west toward his objective on the Flint River. Blackshear reported that he arrived on January 6 "without forage and not many rations on hand." Blackshear continued his march, oblivious to the fact that two days later, General Andrew Jackson's command defeated the British at the war ending Battle of New Orleans.

With no instant communications informing him that hostilities had officially ended, Blackshear marched his men, many of whom were sick, south and west from their Flint River base. On January 14, Blackshear received orders to return to Fort Hawkins. Within a week, Blackshear was back at Fort Hawkins, where he begged Farrish Carter, of Baldwin County, to furnish him with 30,000 badly needed rations. Blackshear implored, "Our country is invaded; and I hope in God you will use every exertion in your power to facilitate the movement of the troops to check the insurrection and depredation that will ensue should we delay for want of provisions."

Once resupplied, at least in part, Blackshear began cutting a road down the northeastern line of the Ocmulgee and Altamaha. His destination was Fort Barrington on the Altamaha in McIntosh County. Along his line of march, Blackshear's men cut the legendary "Blackshear Road."

Reports of British activity around St. Mary's were coming in from many sources. One of those sources was J. Sawyer, possibly Jonathan Sawyer the founding father of Dublin, who reported that the British were landing on Cumberland Island. Sawyer wrote Blackshear concerning British atrocities and their movement toward Darien.

By February 4, 1815, Blackshear reported that he was some 132 miles from Hartford or just a few miles from Fort Barrington. Upon his arrival in Darien, David Blackshear reported, "We have been in a constant state of alarm, and the principal inhabitants, remonstrating against my leaving this station."

Just as he was making plans to move toward the enemy, General Floyd wrote to Blackshear, "The official accounts of a peace having been concluded between our country and Great Britain appear to have filled the hearts of the populace here (Savannah) with joy." And, just like that it was over. After formally winding up their affairs, Blackshear's men were discharged and went back their homes in East Central Georgia.

Thus ended the middle and most widely heralded chapter in the epic life of General David Blackshear - soldier, statesman and citizen. Blackshear returned to his Springfield home in Laurens County, where he spent the last twenty two years of his life serving the people of Laurens County and Georgia.